Creating Conservation: Cumberland Island Becomes a National Seashore

The Georgia Conservancy on Cumberland Island, 1967-1972

Not a day goes by when the Georgia Conservancy isn’t, in some form or fashion, focused on the stewardship of Cumberland Island and ongoing efforts to realize the island’s vision as stated in its purpose statement, that:

“Cumberland Island National Seashore maintains the primitive, undeveloped character of one of the largest and most ecologically diverse barrier islands on the Atlantic coast, while preserving scenic, scientific and historical values, and providing outstanding opportunities for outdoor recreation and solitude.”

Cumberland Island is woven into the history of the Georgia Conservancy. From our earliest advocacy efforts to the development of Cumberland’s first GPS trail map to our most recent service weekends, the island encompasses the grand vision of our 55 years and is truly representative of the belief that conservation is never over. Today, just as during our founding in 1967 and long before, there remains the debate over how best to conserve and support this national treasure.

"Cumberland Island in southeast Georgia is considered by the survey to be the best of its type—the low-lying lands separated from the mainland by stretches of marsh and rivers or estuaries.... This ‘sea island’ is thought to contain practically all the desirable features for public enjoyment."

- 1955 National Park Service report, Our Vanishing Coastline

Our story on Cumberland, an island rich in human and cultural history dating back thousands of years, is only five decades old, but it began at one of the most critical periods of Cumberland Island’s history. In the late 1960s, we placed ourselves squarely in the conversations and debates that led to Cumberland’s establishment as a National Seashore, and we haven’t been quiet since.

Towering dunes, lush maritime forests, inland lakes, miles of deserted beach -- 36,000 acres of solitude. The wild island that we know today may seem like a largely untouched relic from the Pleistocene epoch, but the conservation successes that we see and feel today on Cumberland Island did not happen naturally – they were hard fought by citizens, conservation organizations, island landowners, and dedicated elected officials.

By the 1950s, Cumberland, Georgia’s southernmost barrier island had been the longtime estate of the Carnegie family and their descendants - enjoyed by generations of the family as a retreat to wilderness and respite from life in the public eye. Though parts of the island had seen development for family homes and other private amenities, the vast majority of the island had been left to nature’s devices, allowing for a restorative cleanse of the nearly two centuries of agricultural use by the island’s previous planters and owners. By the mid-century, Cumberland was well-known to the Department of the Interior as one of the last remaining examples of large-scale maritime conservation on the nation’s Eastern Seaboard.

Looking to secure their future presence on Cumberland, while at the same time respecting the natural character of the island that they had long enjoyed, Carnegie descendants looked to the Department of the Interior’s National Park Service for options that would lead to the permanent protection of Cumberland Island.

Cumberland Island by Georgia Conservancy Member Milton Bell

Beginning in the 1950s and increasing in the mid-1960s, these discussions eventually grew into the legislation to create Cumberland Island National Seashore, even though the threat of Cumberland Island’s development loomed around every corner.

After our founding in February 1967, the Georgia Conservancy didn’t take long to turn our attention to Cumberland Island. A controversy and subsequent fight over the mining of phosphate in 25,000 acres of coastal marsh in Chatham County in 1968 had drawn the Georgia Conservancy’s stewardship focus to Georgia’s coastal resources. As a result, the Georgia Conservancy took an active interest in Cumberland Island and discussions regarding the conservation of our other barrier islands.

The Georgia Conservancy Board of Trustees added new board members in January 1969, including Cumberland Island landowner Charles Howard Candler III. When the executive committee met in February, Board Chair Norman Smith reported on a Cumberland Island study that the Sierra Club had funded and recommended that the Georgia Conservancy become a “clearinghouse for information on this many-sided issue”, leading to the formation of a coastal “action group” chaired by Georgia Conservancy trustee, Eugene Odum, Ph.D. The group examined ideas for the best use of Cumberland Island, including National Park designation and Wilderness protection.

Early in 1970, prompted by former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, discussions with Cumberland heirs and recent meetings with Georgia Conservancy representatives, Congressman William Stuckey of Georgia’s 8th Congressional District introduced House Resolution 15686 calling for the designation of the entirety of Cumberland Island as a National Seashore. House Interior Committee staff predicted a delay of several years, since other proposals were already pending. But development pressures and State of Georgia proposals soon became an issue, leading the Georgia Conservancy and other partners to engage the public to push for swifter action.

One of those development pressures came in the form of Charles Fraser, president of the Sea Island Pines Plantation on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. A few years earlier, Fraser had purchased 3,000 acres of the island from the Carnegie heirs and began to promote the development of his parcels, all while encouraging the preservation of the rest of the island.

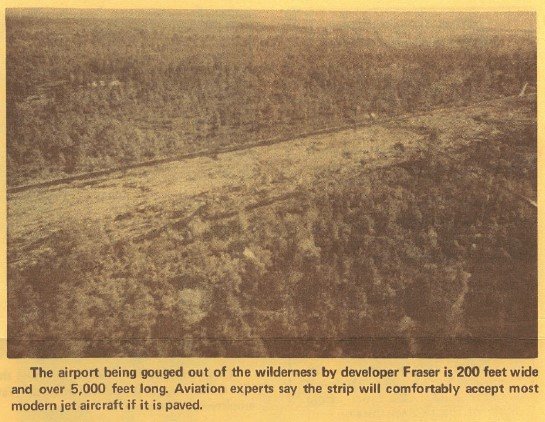

In the spring of 1970, in order to head off the recent attempt by Congressman Stuckey to designate the island as a National Seashore, Fraser secretly began to develop his tract on the north end by clearing land for a mile-long airstrip and two roads. The Georgia Conservancy took notice.

In May, after an investigation by Georgia Conservancy staff and partners confirmed Fraser’s intentions to build communities for private recreation, similar to what he had created on Hilton Head, the Georgia Conservancy’s then-newsletter editor Jim Morrison brought Fraser’s destruction to the attention of our members and the greater public, helping to convince other private landowners on Cumberland and members of Congress that action to protect Cumberland Island from development was now or never.

By June, interest was also mounting to have the State of Georgia acquire Cumberland Island to develop it as an active recreational area. To emphasize opposition to this new alternative approach, decry the efforts of Fraser to develop the island, and promote the conservation of Cumberland by the National Park Service, the Georgia Conservancy worked with 10 other groups to sponsor a massive rally on Jekyll Island. This public showing of support for a preserved and publicly-accessible Cumberland paid off.

Although he engaged the Georgia Conservancy in a heated debate throughout the summer, in September of 1970, Fraser, succumbing to shifting opinions and public pressures, sold the vast majority of his holdings on Cumberland Island to the National Parks Foundation through the financial backing of the Mellon Foundation. The National Parks Foundation would preserve the property for future acquisition by the National Park Service.

Looking West from PLum Orchard's Hunt Camp, Photo By Georgia Conservancy Member Jim Powers

During the next two years, Congressman William Stuckey’s original legislation to create Cumberland Island National Seashore evolved to include greater environmental protections and conservation-oriented provisions. During a public hearing of the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation regarding the second Cumberland bill, introduced by Stuckey and Georgia Congressman Ronald “Bo” Ginn, Georgia Conservancy trustee William Griffin testified in favor of the establishment of Cumberland Island National Seashore. Griffin stated that the Conservancy wanted Cumberland under the custody of the National Park Service, “managing the island in such a way that each visitation is a quality visitation” and that the Conservancy favored giving the Department of the Interior the right of eminent domain so that the whole island could eventually be included under Park Service jurisdiction.

Behind-the-scenes lobbying efforts by another Georgia Conservancy trustee, Jane Yarn, was also effective in strengthening the bill. The final amended legislation to create Cumberland Island National Seashore, passed by Congress and signed by President Nixon on October 23, 1972, included Georgia Conservancy-supported provisions that required the Department of the Interior to conduct a wilderness feasibility study for the newly created National Seashore and that prohibited the building of a causeway to the island.

Cumberland Island By Phuc Dao

Hard-fought efforts to establish Cumberland Island as a National Seashore were successful, but the tangled web of private property and retained rights agreements would have to immediately be addressed during the development of the island’s management plan and wilderness feasibility study. The Conservancy threw itself headlong into the efforts to steer the island’s management toward one that promoted an increasingly wild Cumberland. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Georgia Conservancy Coastal Director Hans Neuhauser, with the help of numerous staff, trustees and members, worked with the National Park Service to develop stronger conservation-minded management processes and refined Wilderness definitions that have led to the greater ecological protection of Cumberland.

In 1982, these efforts paid off when Congressman Ginn, along with Senators Mack Mattingly and Sam Nunn, helped shepherd legislation designating 8,840 acres of Cumberland Island as Federal Wilderness.

Learn more about the Georgia Conservancy’s work on our coast at: www.georgiaconservancy.org/coast